DAVID VINTINER

He then asks me to read a script for a fictitious YouTuber in different tones, directing me on the spectrum of emotions I should convey. First I’m supposed to read it in a neutral, informative way, then in an encouraging way, an annoyed and complain-y way, and finally an excited, convincing way.

“Hey, everyone—welcome back to Elevate Her with your host, Jess Mars. It’s great to have you here. We’re about to take on a topic that’s pretty delicate and honestly hits close to home—dealing with criticism in our spiritual journey,” I read off the teleprompter, simultaneously trying to visualize ranting about something to my partner during the complain-y version. “No matter where you look, it feels like there’s always a critical voice ready to chime in, doesn’t it?”

Don’t be garbage, don’t be garbage, don’t be garbage.

“That was really good. I was watching it and I was like, ‘Well, this is true. She’s definitely complaining,’” Oshinyemi says, encouragingly. Next time, maybe add some judgment, he suggests.

We film several takes featuring different variations of the script. In some versions I’m allowed to move my hands around. In others, Oshinyemi asks me to hold a metal pin between my fingers as I do. This is to test the “edges” of the technology’s capabilities when it comes to communicating with hands, Oshinyemi says.

Historically, making AI avatars look natural and matching mouth movements to speech has been a very difficult challenge, says David Barber, a professor of machine learning at University College London who is not involved in Synthesia’s work. That is because the problem goes far beyond mouth movements; you have to think about eyebrows, all the muscles in the face, shoulder shrugs, and the numerous different small movements that humans use to express themselves.

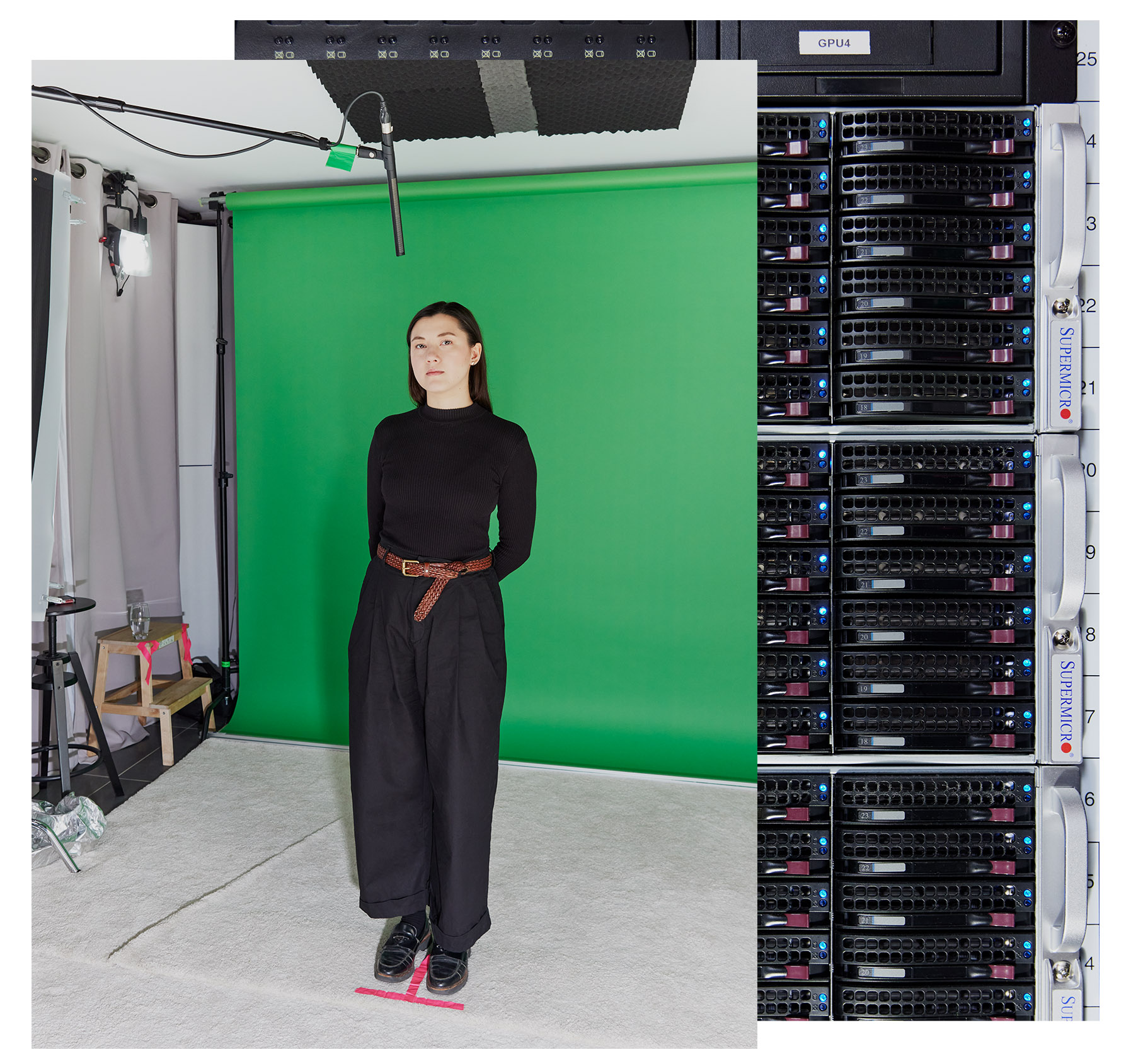

DAVID VINTINER

Synthesia has worked with actors to train its models since 2020, and their doubles make up the 225 stock avatars that are available for customers to animate with their own scripts. But to train its latest generation of avatars, Synthesia needed more data; it has spent the past year working with around 1,000 professional actors in London and New York. (Synthesia says it does not sell the data it collects, although it does release some of it for academic research purposes.)

The actors previously got paid each time their avatar was used, but now the company pays them an up-front fee to train the AI model. Synthesia uses their avatars for three years, at which point actors are asked if they want to renew their contracts. If so, they come into the studio to make a new avatar. If not, the company will delete their data. Synthesia’s enterprise customers can also generate their own custom avatars by sending someone into the studio to do much of what I’m doing.